If you’ve been shopping for an EV lately, you’ve probably heard this line:

“I’m waiting for solid-state batteries.”

It sounds reasonable. Who wouldn’t want more range, faster charging, and fewer battery worries?

But solid-state batteries sit in a weird place. The tech is real. The progress is real. And the hype is also very real.

So let’s make it simple.

This post is about what solid-state batteries actually are, what we should realistically expect between 2026 and 2028, and how to spot the “marketing version” of solid-state.

Why this topic keeps coming back

Solid-state battery talk comes in waves.

One wave is driven by a big promise (like “10-minute charging”). Another wave is driven by a real milestone (like road testing or a pilot production line).

Right now, we’re in a wave driven by milestones.

- Stellantis says it will put Factorial’s solid-state batteries into a demonstration fleet by 2026.

- Mercedes-Benz says it has a solid-state battery test program and has put a lithium-metal solid-state battery car on the road.

- BMW has an i7 test vehicle running all-solid-state cells from Solid Power.

- QuantumScape says it completed key equipment installation for its “Eagle” pilot line aimed at higher-volume cell production.

So yes, things are moving.

Here’s the thing: moving does not mean “you can buy it next month.”

What a solid-state battery actually is (plain version)

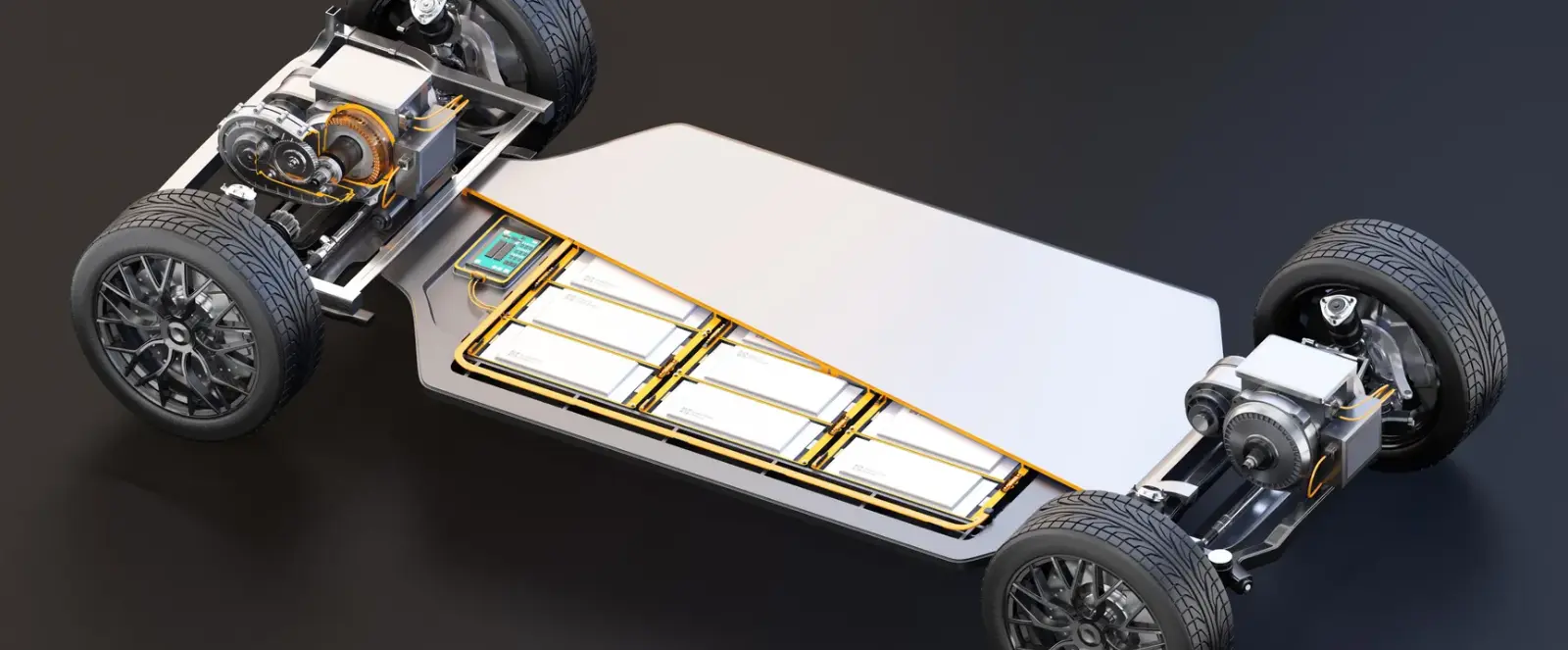

A normal lithium-ion EV battery uses a liquid or gel electrolyte inside the cell.

The electrolyte is the material that lets lithium ions move between the cathode and anode during charging and driving.

A solid-state battery uses a solid electrolyte instead of liquid or gel.

That’s the core idea.

A simple way to think about it is this:

- Today’s cells are like a sponge soaked in liquid that helps ions move.

- Solid-state is like replacing that liquid with a solid layer that still lets ions move.

Some designs also aim to use lithium-metal as the anode, which can increase energy density (more energy in the same size and weight).

Quick jargon translator (one-liners)

- Electrolyte: the medium that lets ions travel inside the battery.

- Energy density: how much energy you can store per kg or per liter.

- Lithium-metal anode: an anode made from lithium metal instead of graphite, often used in solid-state plans.

What solid-state could improve (and what it won’t magically fix)

People usually expect three benefits:

1) Safety (in some designs)

Liquid electrolytes are flammable. Replacing them with a solid can help reduce some fire risk, depending on the chemistry and cell design.

But “solid” does not mean “impossible to fail.” Packs can still overheat if cooling fails or if the battery is abused. Think of solid-state as “potentially safer,” not “invincible.”

2) Faster charging (maybe, under the right conditions)

Stellantis and Factorial claim fast charging from 15% to 90% in 18 minutes for their validated cells.

That’s impressive, but there are catches:

- charging speed is limited by the car, the charger, and pack cooling, not just the cell

- heat management matters more, not less, when you charge faster

3) More range (sometimes)

Higher energy density can mean more range for the same pack size.

Stellantis and Factorial cite 375 Wh/kg for their validated automotive-sized cells.

But range is also driven by:

- vehicle efficiency

- tire choice

- cooling and A/C load (very relevant in the Gulf)

- driving speed

So you might see a range bump, but it won’t turn every EV into a 1,000 km cruiser overnight.

Why solid-state is hard (the unglamorous part)

If solid-state was easy, it would already be everywhere.

The problems are not “one small thing.” They are stacked.

Problem 1: The interfaces are tricky

Inside a battery, materials expand and contract with temperature and charge cycles.

Solid materials do not “flow” like liquids. So keeping good contact between layers is hard. Poor contact means resistance, heat, and performance drop.

Problem 2: Lithium-metal is messy in real life

Many solid-state approaches want lithium-metal because it can store more energy.

The challenge is controlling how lithium deposits during charging. If it deposits unevenly, you can get needle-like structures that can cause failure. (Engineers often call them dendrites.)

You can solve some of this with pressure, material choices, and careful charging limits, but that affects cost and durability.

Problem 3: Manufacturing at scale is the real boss fight

It’s one thing to make great cells in a lab.

It’s another thing to make thousands of them, consistently, with good yield, at a cost that makes sense for cars.

That’s why pilot lines matter so much.

QuantumScape’s update about completing key equipment installation for its “Eagle” pilot line is important because it points to the ugly middle step between lab and factory scale.

What’s actually happening between 2026 and 2028 (realistic view)

Let’s separate “you can drive a few test cars” from “you can buy a mainstream model.”

2026: more demo fleets, more road testing

This is the year you will likely see more headlines about cars “using solid-state,” but most will be controlled programs.

- Stellantis says a demonstration fleet is planned by 2026.

- Mercedes-Benz says its solid-state test program has brought a lithium-metal solid-state battery car onto the road.

In real life, it looks like this:

A manufacturer tests a small number of vehicles to validate:

- how the pack behaves in heat, cold, and humidity

- how the charging curve looks after repeated fast charging

- how the pack ages under real driving

- how service and safety procedures work in the field

That’s not mass production. But it’s a necessary step.

2027: some first limited production targets (still not “everywhere”)

Several players talk about 2027 as a serious target for early production readiness.

- Samsung SDI says it aims to mass-produce all-solid-state batteries in 2027 (based on its roadmap and pilot line work).

- Toyota’s public messaging often points toward a 2027 to 2028 window for commercialization, with upstream supply chain work such as solid electrolyte materials and partners.

Toyota and Idemitsu have publicly described cooperation focused on mass production tech and supply chain for solid electrolytes, which is exactly the kind of “boring but necessary” work that decides if this becomes real.

2028: possible first buyer-facing models, but likely premium and limited

Even if a company hits “commercialization” by 2027 or 2028, expect early rollout to look like this:

- higher price models first

- lower volumes

- conservative limits (charging, power) to protect durability

- lots of real-world monitoring

And that brings us to an important point.

Not everyone believes solid-state will replace regular lithium-ion quickly.

Panasonic’s CTO has publicly called solid-state batteries “niche” and pointed to ongoing technical and manufacturing challenges, while lithium-ion keeps improving.

What this means is… solid-state might arrive, but it may not dominate quickly. You could see it live alongside improved lithium-ion for a long time.

The “marketing version” of solid-state (what to watch out for)

This part matters because the term “solid-state” gets stretched.

Sometimes it refers to:

- true all-solid-state (no liquid electrolyte)

- quasi-solid or semi-solid (some liquid or gel still present)

- a normal lithium-ion cell with a slightly different electrolyte mix

So when you hear “solid-state,” ask one simple question:

Is the electrolyte fully solid, or partly liquid/gel?

If the answer is fuzzy, treat the claim carefully.

5 ways marketing can mislead without technically lying

- Using “solid-state” as a vibe, not a definition

If they can’t explain the electrolyte in one sentence, it’s probably branding. - Quoting “range” without pack size

A bigger battery can produce a bigger range even with normal cells. - Quoting charging time without conditions

Was it on a warm pack? What charger power? What percent window?

Stellantis, for example, states a specific window (15% to 90%) which is a good sign of seriousness. - Showing a prototype and implying mass production

A single test vehicle is not proof of scalable production. - Ignoring cycle life

Cycle life is how many full charge-discharge cycles the cell can handle before major capacity loss.

Factorial’s public numbers mention over 600 cycles, which is a useful data point, but it still doesn’t answer everything about 8 to 10 years of real ownership.

Should you wait for solid-state in the UAE (honest answer)

If your car is fine today and you simply want the “next best thing,” waiting can feel smart.

But if you need a car now, waiting can become an endless loop. Because after solid-state, you’ll hear about sodium-ion, silicon anodes, LMFP cathodes, and so on.

Here’s a practical way to decide.

Waiting makes sense if:

- you do not need a car in 2026

- you want a premium model anyway

- you are okay being an early adopter of a new battery type

- you can tolerate unknowns (resale value, service processes, replacement costs)

Buying now makes sense if:

- you need a reliable daily car this year

- you can charge at home or work

- you want proven service support

- you want predictable ownership costs

In real life, it looks like this:

A buyer in Dubai who drives 80 km a day and has home charging will get more benefit from a well-supported EV today than from waiting two years for a battery type that may debut in limited models first.

One UAE-specific angle people forget: heat

Solid-state batteries are often discussed like they automatically solve temperature issues. They don’t.

They still need thermal management. And in the Gulf, your thermal system is doing heavy lifting for most of the year.

Stellantis and Factorial cite operation from -30°C to 45°C for their validated cells.

That’s useful, but UAE summer conditions can exceed 45°C ambient, and battery temps can climb higher under load. So pack cooling design still matters a lot.

What to watch for in 2026 (signals that actually matter)

If you want to track real progress without getting pulled into hype, watch these:

- Demo fleet results

Not just “it exists,” but what happened after months of fast charging and heat exposure. Stellantis putting cells into a demo fleet by 2026 is a meaningful milestone. - Pilot line output and consistency

QuantumScape’s Eagle line milestone is about moving toward higher-volume processes. The next question is consistency and yield, not just installation. - Who is building the supply chain

Toyota and Idemitsu talking about pilot facilities and supply chain for solid electrolytes is a signal of “we’re trying to make this manufacturable.” - Warranty language

When solid-state becomes buyer-facing, warranties will reveal how confident manufacturers really are. - Service readiness

High-voltage safety is not optional. A new battery type will need new handling and diagnostics. Early buyers should expect more dealer involvement at first.

A quick reality check to end on

Solid-state batteries are not a scam. They’re not magic either.

Between 2026 and 2028, the most likely outcome is:

- more test vehicles and demo fleets

- limited early production in higher-end segments

- continued improvements in today’s lithium-ion that close some of the “solid-state gap” anyway

So if you’re buying an EV in 2026, don’t buy based on a battery that is not on the lot yet.

If you only do one thing, do this: choose a car that fits your charging life today, with strong local service support, and treat solid-state as a future upgrade, not a reason to pause your life.